Joni Mitchell was one of the greatest songwriters of the 20th century, full stop. Frequently, praise of Joni will add the "female" qualifier to that sentence, and while that is technically true I also think it somewhat unnecessary. Joni Mitchell's first eight studio albums are, in aggregate, an elite body of work, and while she certainly fell off some later, she also deserves credit for consistently trying to stretch herself beyond the stereotypical sound and image people built up of her. She is an easy **** artist for me, and I can absolutely see a possibility where she grows further for me and I end up upgrading one or more of her albums such that she someday qualifies for *****.

What's curious for me, though, is that it took me so long to have enough of an interest in her to reach this conclusion, and I'm not entirely sure that this is all my fault. Joni Mitchell was a popular and critically acclaimed artist in her heyday, and certainly many prominent musicians (male and female) in subsequent decades recognized her greatness and cited her as a major influence, but I feel like she hasn't really remained as one of the first names casual fans of the 60s and 70s think of or rave about when they think of great songwriters and musicians. "Both Sides Now" (an extraordinary song, mind you) absolutely dominates the public memory of her to the extent that the public has a memory of her, and people who pay attention to lists of critically acclaimed albums might notice that Blue (and maybe Court and Spark) consistently shows up somewhere on "top ### albums of the 70s / all-time" lists, but there's not the same deafening intensity of recommendations from the music public writ large to get a lot of her best albums as there is, say, with Bob Dylan or Neil Young, two of her contemporaries to whom she is often compared. Part of this might be that she didn't have a major "comeback" period in the 90s onward equivalent to what those two did, but even if we disregard a lot of the inherent sexism that goes into pushing her aside (and I'm not saying we should disregard it generally, but I don't want to dwell on that this instant), I think some of it is that lumping Joni into the Dylan/Young category does her a disservice.

I generally (even if not always specifically) adore Dylan, and I generally (even if not always specifically) love Young, but while Joni could never match Dylan/Young in terms of what made them specifically special (Mitchell had no interest in actively trolling her audience in the way Dylan did, for instance), they couldn't match Joni in terms of what made her specifically special either. Joni Mitchell was a master of creating and playing deceptively intricate and unusual songs on both guitar and piano (on guitar in particular, the innovations she came up with to get around the limitations imposed on her by a childhood bout of polio deserve mythologizing every bit as much as Tony Iommi de-tuning his guitar to cope with losing his fingertips), overlaying her songs with lyrics (from a distinctly feminine perspective) that made you think without making you wander a labyrinth of word games (mind you I love those word games from Dylan) and that could make you feel things deep in your soul. In her best works, she consistently displayed what I could describe as a "taut looseness," a controlled bit of jazziness and looseness that nonetheless always felt in control and never felt like it might go off the rails, and while I could see somebody (wrongly) assessing this as "her songs are rambling and not catchy enough" I think that misses how her songs work at their best. But that's for the reviews themselves. Joni Mitchell is amazing, and not bothering to get acquainted with more than a couple of her albums before I reached my late 30s is yet another example of how I keep getting in my own way in terms of finding music that I love.

A brief note: as of the start of this page (in April 2022), I am aware of the ongoing project known as The Joni Mitchell Archives, for which (as of writing) two volumes (1963-1967, and 1968-1971) have been released (with the expectation that more will come). My understanding is that these are absolutely essential listening for better understanding her general creative process during these eras and that they provide a lot of otherwise unreleased material, and one might reasonably think they should be covered here. For my initial pass through this page, I am not going to attempt to review or process these albums, but I would like to come back to them at a later point.

Best song: Night In The City, Song To A Seagull, or Cactus Tree

Don't do this. Joni would certainly record much better albums than this in the future, but this is still a terrific debut that immediately establishes Joni as a rare talent. Broadly speaking, this album is actually two suites: the first side is subtitled "I Came to the City," while the second is subtitled "Out of the City and Down to the Seaside," and both sides range from good to astounding. The first track, "I Had a King," is somewhat straightforward by Joni standards in a certain sense (it's about the breakdown of her marriage to Chuck Mitchell, whom she had divorced earlier in 1967 and probably should never have married in the first place), but it immediately shows a majesty that she could conjure up in both her voice and the music that few at the time could have matched, and I think it's a fantastic start to her career. My favorite track on the first side is the delightful piano-based "Night in the City," which for me always conjures the image of somebody gleefully walking past brightly lit up buildings and passing under a street light every time she goes high in the chorus of "Night in the *Ci*ty looks pretty to me," but the other tracks aren't far below it. "Marcie" (about a woman waiting for man she pines for to write her back before saying screw it and getting on with her life) was an immediate standout for me (especially the amazing way she sings "Like string and brown *pa*per"), but "Michael From Mountains" (another song about longing for somebody who won't give her the attention she might hope for) and "Nathan la Franeer" (a solid dark acoustic number despite having the most obvious production flaw on the album) are both remarkable in their own way.

The second half is generally similar in quality, with a couple of major standouts supported well by the other material. "Sisotowbell Lane" (Joni claims "Sisotowbell" stands for "Somehow, In Spite Of Trouble, Ours Will Be Ever Lasting Love," and I'm not sure if this is earnest or trolling but it actually works with the theme of the song) is a deeply pleasant song about a longstanding contented love, with two people passing the time by taking turns in their rocking chair and eating muffins and berries that turn their tongues blue, and it might be one of the most charming things she ever wrote. "The Dawntreader" (which might be connected to C.S. Lewis' _Voyage of the Dawn Treader_ but maybe not) is much more about melancholy majesty than about going somewhere in its 5 minutes, but it's an absolutely entrancing melancholy majesty so I'll take it, and "The Pirate of Penance" (which has Joni occasionally in a duet with herself to great effect, like when she sings "She dances for the sailors in a smoky cabaret bar underground), while clearly a relatively minor track on the album, is still a lot of fun.

All this is just setup, though, for the amazing last two tracks. The title track starts with a quiet but firmly plucked guitar that can't help but grab my attention immediately, and ends with one of the grandest sternly played acoustic guitar chords I can imagine, and in the middle is a terrific rumination of how her dreams and ambitions are much less in line with the confines and requirements of conventional society and much more in line with the freedom she observes with birds she sees down by the beach (favorite line: "But sandcastles crumble and hunger is human / And humans are hungry for worlds they can't share"). I can't prove this, of course, but I can't help but wonder if this song was on the radar of ABBA when they put together "Eagle" many years later, and that possibility can only help this song for me. And finally, "Cactus Tree" is simultaneously sad, regretful, optimistic, and defiant all at once: roughly speaking, the song is an acknowledgement of all the men who have loved her and will love her, and a concession that she might ultimately love them too, but that she can't promise that she will love them back in a way that will satisfy them, because trying to make sense of all the opportunity in the world and her place in it might make it hard for her to accommodate somebody else when trying to figure out your own life is hard enough on its own (there's more to it than that, of course: with Joni there's always more). Set to music that somehow manages to capture and magnify all of the emotions of the lyrics, while still being crisp and immediately memorable in a way that Joni doesn't always prioritize, this makes a terrific closer and launching point for the rest of her career.

If you come to this album from later in her career, I suppose there's a chance you could find it a little underwhelming, but if this had somehow been her only album it would still be worth people's attention. Hell, if you started with a later album and couldn't get it into it, this might be a great next stop, because hearing her in a slightly dialed-back version might be just the primer you need to help get acclimated to the approaches she would take later on.

Best song: Both Sides, Now

The most famous songs, of course, are "Chelsea Morning" and "Both Sides, Now," both of which Judy Collins had previously covered and both of which sound far better in Joni's hands. "Chelsea Morning" is a marvelous track 2, a bouncy, chipper song (with a delightful chorus of multiple high-pitched Jonis jumping in during the final verse) about living in the Chelsea neighorhood in New York City, surrounded by other ambitious artists, and in particular it draws from the colors that would bounce around her apartment in the early morning from a stained glass mobile which she had cobbled together from people's discarded trash. And "Both Sides, Now," well, that's just one of the best songs ever written, a song about how once you move beyond the easily understandable cliches associated with the physical/emotional/philosophical world, you can't help but realize just how little you actually understand, and framed within one of her most memorable melodies and most striking arrangements (it's all about the little details in the acoustic playing) she'd ever put together. I don't know if "Both Sides, Now" is actually her very best song ever (it might be but I don't think it's a runaway winner; Joni wrote a lot of great songs), but it's an absolute stunner regardless.

So what about the rest? "Tin Angel" sounds a lot in mood and function like "I Had a King" from the debut to me, as she wrestles through an internal conflict driven by her thoughts about an old relationship vs her current one, and I don't quite love it as an album opener, but I do really enjoy the moments when the stern facade falls away to reveal something gentler. Much better for me is "I Don't Know Where I Stand," where Joni feels a pull to yield her emotions more fully into a new relationship but also feels a sense of doubt and fear (not only about her own feelings but what she thinks the feelings of the other might be) that makes her act cautiously, and it's definitely one of the best and most beautiful expressions I've heard of the stresses people inflict on themselves in trying to find connection with others. "That Song About the Midway" is apparently about her relationship with Leonard Cohen, with whom she had a torrid love affair upon meeting him in 1967, and I find it fascinating that they were able to stay friends afterwards, because the man described in this song is someone she's overwhelmingly attracted to but spends much of his time luring in other women with the power of his voice and raw energy: I don't find the song especially amazing, but I understand why somebody could. Closing out the first side, then, is "Roses Blue," an interesting ball of acoustic tension (it's about somebody who's really gotten into the occult and ends up unable to function without it) with a great additional guitar placed on top of it for effect (the hell is that, a balalaika? I genuinely don't know), and while a small part of me thinks it could have been shorter (it's only 4 minutes but I can't shake the feeling that a 2 minute version of this would have given this album some interesting tension that could have helped it), I still enjoy it a lot.

The second half, aside from "Both Sides Now," consists of four songs that I'm pretty sure I like a lot individually but that I find somewhat befuddling as a set, which is good and bad. Lyrically, "The Gallery" is apparently another one inspired by her Leonard Cohen relationship, and once again the lyrics leave me baffled that they could remain friends: "I gave you all my pretty years / And I was left to winter here while you went west for pleasure / And now you're flying back here like some lost homing pigeon / They've monitored your brain, you say, and changed you with religion" hits differently when you know about Cohen's brief fling with Scientology. "I Think I Understand" is much gentler, with a pleasant but not especially striking delivery in the verses but a tour de force delivery in the chorus, especially given how brief it is (seriously, the way she sings "I think I understand / Fear is like a wilderland / Stepping stones and sinking sand" can stay in my head forever if it wants), while "Songs to Aging Children" is also very gentle but has a fairly wild arrangement of layered vocal Joni, and while I enjoy it I find it oddly unsettling. And finally, "The Fiddle and the Drum," which comes right before "Both Sides, Now," is 3 minutes of a capella anti-Vietnam protest, and while I'm pretty sure it's great in its own right, it also leaves me feeling completely dislocated in a way that's only remedied by the opening chords of "Both Sides, Now" (and maybe that was the point).

I do admire how Joni clearly made so many deliberate moves to stretch herself for her second album, but I also think she was still in more of a feeling-out period than she would have realized at the time, and it's peculiar to me that all of those deliberate moves to stretch only amounted to a lateral move in quality. And yet, she didn't decline with these changes either, and in the ways she stretches here (in arrangements, in complexity of vocal melodies, in emotional ambiguity), I can definitely hear her sowing the seeds for much of what would come later. This is worth getting early because of "Both Sides, Now," but don't make the mistake I made in just getting this and Blue and stopping there for way too many years.

Best song: For Free or Woodstock

Indeed, as much as I generally enjoy her first two albums, hearing this album right after the previous two somewhat reminds me of when I watched an HD TV feed after spending my life to that point accustomed to SD. This album offers a great deal more sonic variety than its predecessors: where the first two albums were largely acoustic guitar albums with an occasional touch of keyboards to provide a change of pace, this one is much more balanced between guitar and keyboards, and this album also contains a cello and some woodwinds that provide a lot of color. I wouldn't exactly say that I think this album sounds better because this instrumental approach makes the sound more "sophisticated," but I would say that there's an energy and vibrancy here that Joni couldn't quite unlock with the more limited set of tools she used before. I have read critique of this album for its clear move away from more immediately memorable melodies, but the gains in emotional impact and instrumental atmosphere are much more than enough to compensate for me, and they help make the album into a great experience for me.

The album has somewhat odd sequencing: the album ends with three of her most famous songs, but up to that point the album doesn't bother with anything remotely approaching a hit, instead simmering at a low boil with songs that range from "this is quite nice" to "holy hell this is an awesome deeper cut," and honestly I kinda like the implicit challenge in this approach. The best song in the first half, and one of my favorites she ever did, is "For Free," a song I first heard in a cover done on the Byrds reunion album (I still like that cover quite a bit), but which goes way beyond that in its original form. At first pass, the song (done as a slow melancholy piano ballad except for when a clarinet briefly pops in) is about a famous musician observing a street performer not making any money, but of course there's more to it: the song is more about the famous musician herself, longing for the innocence and connection and joy that comes from playing music just for its own sake (the most painful moment of the song is when she thinks about going over, asking for a song, and harmonizing along, but instead has to walk away because she's on a schedule), but instead having to partake of the good and bad that comes from doing music as your profession at a high level. It's a song about music, but like so many of Joni's other best songs, it's a song about feeling like you've lost something that you can never get back, and it rattles me every time I hear it.

The rest of the first half doesn't quite measure up to "For Free," but I still enjoy it a lot. The opening "Morning Morgantown" is a tribute to the good aspects of American small-town life (milk trucks, a gentle pace that allows you to sit and sip lemonade, strangers saying hello to each other) while completely ignoring the darker sides (honestly I'm fine with that, not everything needs to be a dark exploration of the American soul), and the piano part that it centers around is bright and cheery in a way that always puts me in a great mood immediately. After "For Free" comes "Conversation," a song about a woman who serves as regular confidant (especially about relationship difficulties) to a man she's fallen for, and how she both hopes he'll eventually pick her and also has to carefully conceal her feelings both to him and his partner. "Love is a story told to a friend / it's second-hand" and "She speaks in sorry sentences / miraculous repentances / I don't believe her" are among many great lyrics here, but this song isn't just about lyrics; the acoustic base (with a marvelous vocal melody on top of it) eventually gets covered in a great combination of multiple Joni "doo doo doo" voices and jazzy flute + saxophone that gives the song a terrific pep in its step to the very end. The title track finds the guitar weaving a figure that I always instinctually want to describe as "mystical," and I find it fascinating how the song talks about three of Joni's friends in a way that makes them feel like they belong more in a well-written fantasy novel than in real life, but also implicitly suggests that there's something about the nature of the canyon (in this case Laurel Canyon, a neighborhood in Los Angeles) that makes half-real/half-mystical people like this a possibility in the first place. "Willy" is a song about Graham Nash (his middle name is William), with whom Joni paired up for a while (more on that later!!), and it's such a gentle piano-driven song of total contentment and bliss that it breaks my heart every time I hear it (given what we know now): the line "Willy is my child, he is my father" that begins and ends the song could make somebody raise an eyebrow, but if you parse it as something like "Willy is my Omega, he is my Alpha" it makes more sense. And finally, the first side rounds out with "The Arrangement," a directionless piano haze about how life gets swallowed up in the pursuit of things and titles; the ending lines of "You could have been more than a name on the door / You could have been more ..." always hit me less as an interesting musical idea in and of themselves and more as a dying whisper of regret, and this song always leaves me shook at the end.

The first three tracks of the second half are essentially more of the same, and while I don't love these songs I still think they're good enough. "Rainy Night House" starts the second side with the same sort of piano melancholy that "The Arrangement" used to end the first side, and it's another song about how hard she fell for Leonard Cohen (even if the song uses other people as proxies for them): the best moment of this one is when Joni sings "I am from the Sunday School / I sing soprano in the upstairs choir" and a Joni choir answers with "Aaah-aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaah." The following "The Priest" (this time a dour acoustic song) is also often interpreted as about her time with Leonard Cohen, and in a certain sense this is where the album starts to tire me a bit, yet the final verse ("Oh come, let's run from this ring we're in / where the Christians clap and the Germans grin / saying let them lose, crying let them win / oh make them both confess") is so deeply unsettling that it ends up making the song worth it for me. "Blue Boy," then, ends the long stretch of deeper cuts with another melancholy piano ballad, about (I'm admittedly guessing here) a romance that ultimately falters because of the man's emotional distance from his woman: she longs for him until he comes home one day and finds she's lost her ability to care for him: this is probably my least favorite on the album, but again, it's still a long way from bad.

And then, all of a sudden, the album (relatively) turns into a hit parade. "Big Yellow Taxi" is a chipper environmental protest anthem on the surface, about needing to care for trees or not using DDT that kills bugs, but more broadly it's tied into the chorus lyric, "Don't it always seem to go / that you don't know what you've got 'til it's gone?": the title of the song, after all, doesn't come from the environmental lyrics, but from a near-throwaway line near the end where "a big yellow taxi took away my old man" (whether he desired this or was taken by the law is a matter for interpretation). The juxtaposition between the serious message of the words and the chipper nature of the music always cracks me up, especially the final way she sings "They paved paradise, put up a parking lot," and this deserves every bit of its classic status. The album closer, "The Circle Game" (written as a response to the Neil Young song "Sugar Mountain"), wasn't released as a single, but it did get covered a lot, and it strikes me as an ideal balance to the opening "Morning Morgantown," a gentle contemplation of the broader meaning provided by the smaller, simpler aspects of life we might otherwise take for granted in the moment.

Sandwiched between these, then, is "Woodstock," and dammit, if you prefer the Crosby / Stills / Nash / Young version of this to Joni's version, I don't know if I can trust you. Mitchell didn't appear at Woodstock for various logistical reasons, but she took inspiration from the idealism built into the concept of the festival, of people gathering from far and wide to merge their souls through the power of music as if they were returning to the Garden of Eden, and she built a towering moody epic out of this. Joni's electric piano, as well as Joni's choice to accompany herself with a Joni army after each chorus, won't make for as immediately pleasing of an experience as will the CSNY cover that has dominated classic rock radio since, but hearing Joni sing "We are stardust / we are golden / and we've got to get ourselves back to the garden" shakes me in a way that the more polished (and let me be clear, the cover is fine) approach just can't.

Again, I don't think this is the best Joni album, and it's certainly not one of her most accessible, but weirdly, if I could do it all over again, I wish I had gotten this one first. If you've dabbled in Joni and haven't gotten into her (maybe you've just listened to Blue and didn't get the appeal), give this one a try and see if it breaks through: there is a lot to admire here, both with individual songs and with how it holds together overall.

Best song: Little Green or This Flight Tonight

Blue is an explosively emotional album, and part of the reason has to do with her ongoing relationship intrigues (in the time between Ladies of the Canyon and this, she broke off a lengthy relationship with Graham Nash, then entered an intense relationship with James Taylor only for him to break up with her once he became very famous), but this album also acknowledges the pain that related to giving up her daughter for adoption a few years earlier (the details of this only became full public knowledge about 20 years later). More generally than covering specific episodes of her life, this is the album that most clearly shows the listener the absolute emotional roller-coaster of being Joni Mitchell in her late 20s, for better or for worse, but this isn't just a case of intense voyeuristic confessional: the flood of emotions provided by this album is framed in a crispness in her melody writing and song structures that wasn't always the case for her on other albums, and while I'm certainly an enthusiastic supporter of the atmospheric intrigue that Joni could muster up on other albums, I must say that this extra level of compositional discipline (whether it was deliberate or not) suits her well. That's not to say that this album is a wall-to-wall collection of potential singles or anything, nor would I want it to be, but there's something very appealing to me about the control and punchiness provided by this album relative to some of her others.

The first half of this album, in terms of tone, has three generally chipper (but startlingly deep when you look closer) tracks and two tracks that are about as sad as Joni Mitchell could get. The opening "All I Want" is about trying to balance the happiness one can find in a relationship with the absolute joy and glee that can come from the freedom that life can offer you in other areas: on the one hand, you have lines about wanting to be closely intimate with somebody ("I want to talk to you, I want to shampoo you / I want to renew you again and again" is amazing in this regard), and on the other hand, you have lines like "Alive, alive, I want to get up and jive / I want to wreck my stockings in some jukebox dive" about joyful living, all tied together with "I am on a lonely road and I am traveling / Looking for the key to set me free / Oh, the jealousy, the greed is the unraveling / It's the unraveling and its undoes all the joy that could be" which brings out how these two general desires are largely at odds with each other. This tension is amplified by the battle between the relatively tight melody and the way Joni keeps trying to stretch the structure as far as she can (like how she repeats the word "traveling" four times when the song could have gotten by with just one), and the overall effect is stunning once you get to know the details well. "My Old Man" shifts from the guitar center of the opener to gorgeous piano balladry, with lyrics that look back with longing to her relationship with Graham Nash and how she wishes he would have accepted they could be together and happy without the formal boundaries that come with marriage (the chorus line "We don't need no piece of paper from the city hall / keeping us tied and true" is the kicker here), but also with longing for how much she missed him when he was gone and how happy she'd be whenever he returned. "Carey" (featuring a dulcimer), the last upbeat track on this side, is about a fun time Joni had with a hippie community on Crete, while also acknowledging that, even as she was having fun, she couldn't help but think about all of the other places she wanted to go next, and couldn't entirely live in the moment as she contemplated her possible future travels.

The two other tracks have the names of colors in the title, and I don't think it's a coincidence that the first, "Little Green," names a color that is half blue (the title of the album and presumably the color Joni is associating with herself on this album). "Little Green," as people learned many years later (and not by Mitchell's choice), concerned her child Kelly (whose name was inspired by the color Kelly Green), whom she gave up for adoption when she was poor and when she didn't think she could raise a happy child. The song alludes to sorrowing for everything she won't get to see in her daughter's life, and the acknowledgement that the very nature of the world and the passage of time will remind her of her daughter (like when green grass emerges in the spring), while also alluding to the hope for a better life for her daughter than she could have provided. As you might expect, it's done as a quiet acoustic ballad, and it will absolutely rip your heart out if you're not feeling emotionally steeled. The title track, in contrast, is a melancholy piano ballad, and while I wouldn't quite call it a highlight, it's nonetheless a deeply contemplative look at the hollowness that can from a life of only seeking thrills (the line in the chorus "Acid, booze, and ass / needles, guns, and grass / lots of laughs, lots of laughs" is very much not in praise of those things), and it's a fine way to make the listener pause and take stock of their lives as they ready for the second half.

The second half, in terms of tone, has a similar balance to the first half: two acoustic songs (one upbeat, one upbeat until you examine it closely and realize it's pretty sad), two largely melancholy piano ballads, and a song that smashes emotions together in the form of one of the very elite songs of her whole career. "California" and "A Case of You" are the acoustic songs: "California" is another travelogue, full of jumpy glimpses of the fun and energy of Europe while rooted in her longing for home (with some languid pedal steel providing a fascinating contrast to the overall sound); and "A Case of You" is a fascinating lyrical and emotional miasma, refusing to fully commit to one particular vibe or emotion, but all the more intriguing because it's so evocative lyrically (weaving as it does between religious and sexual imagery) and because it's just so damned memorable and infectious. "River" and the closing "The Last Time I Saw Richard" are the piano ballads: "River" is about (roughly) how her feelings about an upcoming Christmas have gotten mixed up with her feelings about her recently ended relationship, and it's about as naked in its pain / sadness / self-loathing as Joni ever got, repeatedly punctuated with the line "I wish I had a river I could skate away on" and occupied with brief quotes of "Jingle Bells"; finally, the closing "The Last Time I Saw Richard" makes a grand effort at tying the whole album together, ending with her in a dark cafe (instead of dancing in a bar as suggested in the opening song) brooding over love as a concept, trying so very hard to not lose faith in the very concept of love even as it keeps bringing her pain (there are other interesting aspects to the song, not least of which is the fate of Richard as he sold out in joining middle class America), and it's a great capper.

In the midst of this, however, is "This Flight Tonight," which became better known through a top-notch Nazareth cover but is a classic in its original form. This song is about regrets in the aftermath of leaving somebody and taking a flight out West to get away from them, and realizing they're committed to this because the plane can't turn around just because of a momentary wavering. The song is as tense and as catchy as anything Joni ever did, but it also has one of the greatest studio tricks in any song of the era: as the song gets to the point when she's listening to the in-flight music station, the sound quality turns tinny to reflect the low-grade headphones that a passenger would be using to listen to it, then immediately snaps back to the regular production style. The song ends with ambiguity, leaving it unclear whether the person will stay out West or make the impulsive decision to drive back (spurred on by moments like how seeing a falling star in her trip made her nostalgic for her man), but I really hope she stayed.

For some people, the force and clarity of this album will manifest themselves easily, and it will be easy for them to see why this album gets regarded so highly: for others, like me, it will take some time and effort, but that time and effort shouldn't be confused somehow with a form of Stockholm Syndrome. Everything I've described above (and so very, very much more) is there and waiting to be found, but for all of this album's emotional intensity, it still doesn't make things immediately easy for the listener to extract them. I wouldn't necessarily start with this album, because I do think there's a danger that (as somewhat happened with me) somebody could find this album oversold if they come into it cold, but it should definitely be one of your first Joni purchases.

Best song: Let The Wind Carry Me

Two of the first three songs are connected to food, which I find mildly amusing: the opening "Banquet" is a lush piano-centric song about record companies getting rich and fat while the actual artists are left to pick off the scraps, even the ones who have ostensibly "made it," while the third track, "Barangrill," is about ... well, I'm not entirely sure what it's about, but it seems in some sense about being at a restaurant and realizing that even the waitresses and the truck drivers stopping in, all people that society has deemed "unimportant" in some way, are all in possession of great wisdom about something or another. In between these tracks comes "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire," inspired once again by James Taylor and his heroin addiction, and I'm really taken by the simultaneously seductive and dangerous mix of the acoustic guitar and the various woodwinds (and boy is there something really striking about the way she sings "You can come now or you can come later"). "Lesson in Survival" is a piano number with more than a bit of "The Last Time I Saw Richard" in its DNA, but this time it's back to themes of simultaneously wanting independence and wanting connection and the inherent tension of these desires; there's a lot of greatness here, but it's the ending line "I will always love you, hands alike / Magnet and iron, the souls" that always flattens me most. The side-ending title track is an acoustic ballad that seems to be about the difficulties of loving a famous person and having to share them with the world, and it's really good (even if I'm also sure that I'm probably missing three levels of subtext that somebody else might notice), but my absolute favorite of the album is "Let the Wind Carry Me," which comes right before it. "Let the Wind Carry Me" is a look back at Joni's time as a teenage girl in the early 60s, with no less of an independent streak back then than she would have as an adult, with images of her mom objecting to her fashion and makeup choices (her father in contrast is inclined to give her more leash), and it's an incredible combination of moody piano lines, moody atmospheric saxophone parts, and inspired choices in how to sing the lines (if nothing else, you must hear the way she sings the line "she's looking like a movie queen").

The second half, aside from "You Turn Me On etc" (an acoustic guitar number), splits out between three piano songs and two acoustic guitar songs, basically matching the balance of the first half. Among the piano songs, "See You Sometime" is another attempt to work through her James Taylor feelings, including her hesitancy to fully commit to him while feeling jealous of him not fully committing to her; "Blonde in the Bleachers" is another song about having a relationship with a musician and having to fight with the public for his affection and attention; and the closing "Judgement of the Moon and Stars (Ludwig's Tune)" is Joni's affectionate ode to Beethoven (in addition to the lines alluding to his need for constant self-expression I'm amused at the line "You've got to shake your fists at lightning now," which legend says he did just before he died, though this is historically dubious). Among the acoustic guitar songs, "Electricity" vaguely seems like it's about somebody who's emotionally broken and who needs to be fixed like she's a machine, but hell if I know for sure; and "Woman of Heart and Mind" is about loving for somebody despite (and maybe because of) their flaws, with one of my favorite lines she ever wrote ("You know the times you impress me most / are the times when you don't try") and one of the most hilariously laid-back f-bombs I've ever heard.

Looking at this review, I'm not sure it fully matches up as written with the rating that I've given the album, but the thing is, this is music that almost actively defies writing about it; so much of what I love about this album is a sort of indescribable magic, almost as if I experience it in a dream where, upon waking, I can only catch the general vibe but not many specifics. This is a difficult album, in many ways much more so than the albums that immediately surround it, but it's incredible, and it's absolutely essential.

Best song: Free Man In Paris or Down To You

Perhaps more than with any of her albums since the debut, each of the two sides feels like a suite, even as the individual songs also hold up extremely well. The hit single from this side was "Help Me" (in the track two slot), a song that returns to one of Joni's preferred themes (simultaneous enthusiasm and caution as she enters yet another love affair), and while this might have worked on an earlier album with a more sparse arrangement, here the sonic cornucopia that comes from the electric guitar, the woodwinds (both the flutes and the subtle saxophone), the horns, and the multiple Joni layers lifts it into the heavens. The opening title track begins with atmospheric piano lines much like many great tracks from her have to that point, but then the arrangement just gets deeper and deeper (bits of pedal steel, some well-placed chimes near the end, just enough percussion to hold the song together), as Joni delivers lyrics loosely inspired by an encounter she had with a man who was convinced she had written many of her songs specifically for him. "People's Parties," in only 2:15, delivers an absolutely inspired knockout (with an effortlessly light-on-its-feet acoustic-based arrangement) about a topic I can empathize with broadly (even if not with the specific details): the unease that comes from being in a social setting with people who are all deliberately hiding their true selves, and wishing she could just be normal but not knowing how to pretend like they do (it also has one of the all-time great Joni lines: "One minute she's so happy, then she's crying on someone's knee / Saying laughing and crying, you know it's the same release").

"The Same Situation," which flows out of "People's Parties" without a break, is a lush piano-based number about (among other things) trying to find real meaning in a world whose values seem to keep getting cheaper, and among many other things it has a line ("Still I sent up my prayer / Wondering where it had to go / With heaven full of astronauts / And the Lord on death row") that hits the struggle of finding this meaning in a world where God is devalued about as well as can be. The very best song on this side and album, though, is "Free Man in Paris," where Joni sings from perspective of David Geffen (a music promoter for Asylum and later the founder of Geffen Records), who wishes he could once again (like he did once in Paris) experience the raw joy of hearing great music and meeting interesting people without dealing with the messiness / politics / insincerity of the music business. Great and insightful lyrics aside (I'm a sucker for a good anti-industry song), the music is as rousing and joyous as anything she ever created, with everything about the arrangement (especially in the guitars, full of subtle atmospheric touches) helping to give a sense of levitation to the sound, and while I understand why it wouldn't have worked as a single, I have to rate this easily as one of her best songs.

The second side might be a touch below the first in overall quality, but only a touch. There are a couple of fascinating twists that land a long way away from anything Joni might have considered including on previous albums, and I find them an absolute riot: "Raised on Robbery" is a funny old-timey rock song (with Robbie Robertson of The Band on electric) about a woman using her feminine wiles to get something out of a guy in a hotel lounge who just wants to watch the Maple Leafs game (which he's bet some money on) in peace, and the closing "Twisted" is a cover of a 1950s jazz song (with a guest appearance from Cheech and Chong!) about psychoanalysis, and Joni gives a hilarious vocal performance (Joni once described the song in the context of the album as an encore, and as somebody who feels that more serious albums should have encore tracks I'm all for it) that I look forward to every time. "Trouble Child," which comes immediately before "Twisted," is a little bit lumbering in the verses. built around the main low-key guitar riff, but it also becomes low-key cathartic and cleansing in the chorus ("They open and close you / Then they talk like they know you / They don't know you" is sung in a way that can stay in my head forever), so while it's my pick for the album's weakest track, I still think it's quite good on the whole. Earlier in the side, "Car on a Hill" (which rules) builds from a low-key burner in the verses to an expansive wash of sound when Joni layers her mournful vocals over menacing/weeping guitars, and "Just Like This Train" stays as a low-key gentle song supported by dreamy electric guitars (with ascending woodwinds popping in as needed) while Joni sounds great singing about who knows what, but what comes between them, the 5:38 "Down to You," is the best song of the side and nearly neck-and-neck with "Free Man of Paris." This one starts in familiar territory, with Joni doing a melancholy piano ballad akin to something on Blue, but when the mood shifts, it shifts: Joni brings in a clavinet to great effect in the bridge, which touches on the desperation and tension and slight anger that comes in a one-night-stand, and when Joni later sings "You brush against a stranger and you both apologize" she does so in a way that really gets at the sadness that comes from not having real connection with anyone. The middle of the song is given over to string and horn parts that might have gotten gloppy on their own had they gone too much longer, but when they get layered with the piano and the clavinet, they create an amazing sound that is oh-so-70s but is so very much in my taste wheelhouse.

I came to this album much later than I came to Blue, and thus it hasn't had as much time over the years to burrow into me the way that many of my other favorite albums have, and at this point, if I listen to these two albums back to back, there's a focus and crispness to Blue that makes me prefer that one to this. With that said: had I gotten into this album in my 20s, there's a chance that this would have become absolutely foundational to my music tastes as a whole, and thus I have to wonder if there's a possibility that this one will grow on me even more than it has. If I still care about this stuff in my 60s as much as I still do in my early 40s, when I will have sat with this album as long as I've currently sat with Blue, it's possible I may ultimately move this one ahead of Blue. Whatever may be, this is a jaw-dropping album, and an absolute necessity for any serious collection of 70s pop music.

Best song: many

There isn't much to say on a song-by-song level, of course: aside maybe from the two new tracks (which I don't especially mind), there's nothing on here that was even close to a weak track in the original version, and the reinterpretations from Joni and her band consistently find subtle new angles that bring out charms and emotional power that I didn't necessarily always catch in the originals. If you like Joni and don't dislike the concept of live albums, I can basically guarantee you'll enjoy this a lot.

Best song: Shades Of Scarlett Conquering or Harry's House / Centerpiece

And dammit, I love it. It's not a perfect analogy, but this album kinda sounds to me, in the context of Joni's career, like what Stevie Wonder's Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants would sound like if that album was actually successful; after Court and Spark, Joni was at an all-time high terms of earned goodwill, in much the same way that Stevie was at an all-time high after Songs in the Key of Life, and both artists chose to cash in on their goodwill by making their next album into a challenge both for the listener and for the listener's expectations. Where Stevie ended up biting off way more than he could chew in terms of length and overall musical approach, though, Joni made an album that may have sounded befuddling at the time (and still does in some ways) but that also sounded extremely prescient in terms of what female artists could potentially achieve in later years (I would suggest, for instance, that Kate Bush and Björk as we know them would not have ultimately happened if not for this album and the next one). It's an extremely easy thing to dismiss this album as a major step down relative to a previous stretch of greatness, but Mitchell was extremely defensive about this album in particular for the remainder of her career, and I don't think she took this position just to be contrarian.

The album's biggest controversy by far, of course, comes in track 2. "The Jungle Line," which centers around a sample of an African field recording of The Drummers of Burundi, and whose music otherwise primarily involves a low-pitched Moog line and Joni singing a somewhat unpleasant vocal part with impressionist lyrics vaguely tied to Henri Rosseau (the famous painter), jazz music (which I think Joni is implying taps into the same creative spirit as Rosseau), and the implied sense of danger tied to city life (I guess this somewhat ties into the African drum line, which may not be the most PC connection a song has ever made, but we'll ignore that for now), would have been an enormous shock to people, but in 2022, I'm largely fascinated by how ahead-of-its-time it sounds. A similar prominent use of futuristic keyboards comes in the closing "Shadows and Light," this time centered around an ARP-Farfisa while Joni sings lyrics about the duality of man in a stark way that reminds me of "The Fiddle and the Drum" (this one obviously isn't a capella but it's nearly there), and again, while this will irritate somebody who wants Joni to just write something resembling a song, this one manages to work for me on the basis of power and conviction.

Funnily enough, the album begins on a somewhat deceptive note with "In France They Kiss on Main Street," a low-key jazz rock song that never had a chance to be a big hit for her (it topped out at 66 in the US) but that does have enough of a hook in the chorus ("And we were rollin', rollin', rock 'n' rollin'") to make it a plausible single release. Lyrically, it's a song that Joni probably could have pushed out in her sleep, an ode to growing up in an era when rock'n'roll was starting to take over mainstream pop culture, but even if it's miles away from the rest of the album in terms of tone I enjoy it a lot (and besides it's impossible for me to resist a song with the line "You could break somebody's heart by doing the latest dance craze"). After "The Jungle Line" comes in to throw the listener for a loop, then, "Edith and the Kingpin" comes in and floats in a jazz-pop haze (with lyrics that do all they can to make you understand this is about cocaine), and it's a kind of song that might completely escape me if not for (a) the way Joni's instincts keep guiding her to make just the right decisions in the specifics of the chord sequences and the arrangements she selects in her role as producer, and (b) the bonkers vocal sound she makes around 40 seconds (and a couple of times later) that gives an intriguing additional sense of tension. "Don't Interrupt the Sorrow" starts off sounding like a pleasant acoustic number with congas underneath, but ultimately the cool moody guitar snaking around in the background becomes the star (even as it maintains a supporting role) while Joni sings about feminine energy ultimately prevailing in a male-dominated society. The best of the side, though, comes with "Shades of 'Scarlett Conquering'" (which Elvis Costello loved in particular), a gorgeous piece of piano-dominated ambience with bits of orchestration (and more incredible layers of guitar tucked in the background) about Scarlett O'Hara (or another southern belle using Scarlett as a generic stand-in); there's nothing resembling a tune here, but the soundscape here is so enrapturing that I completely forgive that and then some (especially in the coda, which I'm sure was one of the main driver of the push to label this music 'pretentious' but sounds like bliss to me).

The title track (which features a co-writing credit with drummer John Guerin), which begins the second side, is more mood music (with a great use of electric piano and some wild backing vocals singing "Darkness" here and there), this time about a woman who stays in a loveless marriage even as she knows that she's more a part of her husband's investment portfolio than anything else, and who isn't entirely sure why she stays but doesn't see much upside to leaving. "The Boho Dance" builds from a few quiet piano chords into a more majestic (but never ecstatic; this album never really strays too far from "mellow" on the whole) collection of various keyboards while Joni sings about the nature of selling out and how even people who claim to reject it secretly feel some jealousy towards those who pull it off (the line "Like a priest with a pornographic watch / Looking and longing on the sly / Sure it's stricken from your uniform / But you can't get it out of your eyes" is especially marvelous). "Sweet Bird" (the penultimate track) is a bit of a stylistic fake-out, a song that never really moves far from its acoustic base (even as the more majestic production, especially in the guitars, makes it clear this wouldn't have belonged with the first two albums), and its lyrics (about how quickly the time of youth slips away) are especially stirring in the context of an album that is so much about the experience of living as a woman. The pinnacle of this side, however, falls smack dab in the middle: "Harry's House / Centerpiece" addresses a failing marriage, in which the husband can only tolerate life by imagining his wife back when she was young and beautiful (as an idea rather than as a person), and who tries to absolve himself of blame for the failing marriage by telling himself she was just a gold-digger anyway (there's a lot more to the song but this is enough to get started). Deep into the song (a menacing 7-minute atmosphere jazzy epic), Joni brilliantly breaks into a cover of the old jazz standard "Centerpiece," followed by a montage of Harry flashing back to his wife scolding and hectoring him for various things, before coming back into the main song as she tells him and his wealth to go to hell. Again, maybe there isn't much here for people looking for songs, but as an experience, it's breathtaking.

And really, that's how I would summarize the album as a whole. I could see where somebody might decide that if an album demands as much of a listener as this ultimately demanded of me, then maybe it isn't that good after all, but at the same time, even before I could start to make sense of why I liked it, I still felt that I liked it deep in my bones. Absolutely nobody should start with this album, but at the same time, if somebody starts to get into Joni and doesn't see the appeal right away, this is enough of a curveball that it might end up changing your mind about her somewhat. And hey, kudos for once to Pitchfork for giving this a 10.0 grade in a retrospective review; I certainly wouldn't go quite that far, but it's a bold stance in favor of an album that deserves far more love than it's often gotten.

Best song: Coyote or Hejira

Two songs here (both from the first side) are best known today for their inclusion in The Last Waltz: "Coyote" (included in the original movie), and "Furry Sings the Blues" (not included in the original but included in the 2002 re-release). "Coyote," a song (more or less) about a one-night stand (and all of the various emotional consequences and implications of this), was indeed released as a single (it did nothing, which makes sense because there's barely anything resembling a melodic hook), but this is a song whose greatness comes from its sense of frenzied urgency and a feel of road-weariness in both her words and her delivery (it's also the first song on the album to prominently feature Pastorius giving a glorious sense of additional atmosphere). "Furry Sings the Blues" is about her encounter with an old Memphis blues musician named Furry Lewis whom she met in Memphis during a time when Beale Street (a part of Memphis where African American musicians would frequently play) was undergoing a transformation that old-timers didn't especially appreciate, and while Furry didn't especially care for her (which Joni explicitly mentions in the song) or the fact that she referenced him in her song, it's clear that Joni herself absolutely appreciates the history represented by Furry and laments the loss of the past, and her passion makes the song come to life even if it's difficult to recall much about it other than Neil Young's terrific harmonica playing.

Sandwiched between these two tracks is "Amelia," a song where Joni expresses a kinship she feels between herself and Amelia Earhart, especially in terms of the courage needed to make music others might not understand and the courage to fly where others might not be able to help you. As with many great Joni songs, this short summary is woefully inadequate to the task (among other things the song was inspired by a breakup with John Guerin, who appears on much of the rest of the album): the lyrics touch on love and ambition and uncertainty and many other things, and the refusal of the song to resolve in a clear way over its six minutes only amplifies the uncertainty expressed in the lyrics. I wouldn't quite say that this is the best song on Hejira, but as much as any other on here I'd say it's one of the songs that most strongly defines Hejira.

The first side is rounded out by "A Strange Boy," a song she wrote about a relationship she he briefly had with a man (an airline steward) who accompanied her on a roadtrip from L.A. to New England earlier in the year (it's yet another example of the album's skill at creating "unsettled but intriguing" songs, which seems right for a song about the time she spent with somebody who was a great "right now" partner but a bad choice for a "right" partner), and then by the title track, where Mitchell again tries to address her breakup with Guerin and where she put in a tremendous amount of work in crafting the lyrics and the arrangement. Two arrangement details absolutely require mention: first, Pastorius laid down four distinct bass parts for the song, and Mitchell had to make careful decisions about which parts to include at which stage, including when she sometimes let them all play; and second, there's a moment when she mentions "strains of Benny Goodman coming through the snow and the pinewood trees," and she's echoed with the call of a clarinet, the album's one use of woodwinds when that used to be one of her favorite tools. As suggested by the title, this is fundamentally a song about a journey, ultimately ending with her choosing to let love drive her to care again, and it's deeply compelling in the moment even if I still can't fully grok the entirety of it.

Side two doesn't make things any easier. The two middle tracks are "Black Crow," where the main riff almost sounds in parts like a deconstructed version of "Whole Lotta Love" and features a fascinating blend of wild Larry Carlton electric parts and busy Pastorius bass, and "Blue Motel Room," a relatively sedate slow jazz number that features maybe the album's funniest lines as she gives advice to her man about how to fend off other girls who inevitably try to claim him ("I know that you've got all those pretty girls coming on / Hanging on your boom-boom-pachyderm / Will you tell those girls that you've got German Measles / Honey, tell them you've got germs"). These two tracks, however, are just a refuge between two of her most ambitious tracks ever, both of which I consider wildly successful. "A Song for Sharon," which lasts 8:40 and starts off the side, is another one of Joni's "observation" tracks, focusing primarily on various women at various states in their lives and how Joni feels about their places in the world, and ultimately focusing on a woman named Sharon Bell, a childhood friend of Joni who gave up music to become a farmer's wife (basically making her the furthest extreme of what Joni's life could have been had she made different choices). As usual, it is not entirely clear how Joni feels about her own life relative to the women she observes (frankly I'm guessing that Joni didn't entirely know herself), but as usual the point isn't the destination, it's the journey, and this song is one hell of a journey both lyrically and musically. And finally, "Refuge of the Roads" details a visit Mitchell made to a controversial Buddhist teacher whom she claimed got her off cocaine (as well as other aspects of her journey before and after), but as interesting as her travelogue (and her passionate delivery) might be, the star of this track is clearly Pastorius, who gives Joni's already interesting guitar chords a shot of adrenaline every time he emerges prominently and makes the track feel otherworldly.

Hejira is not an album I would recommend for everybody who otherwise likes Joni Mitchell, but much like with Hissing of Summer Lawns, it's an album I would definitely recommend to somebody who's on the fence about her. This is the album, in many ways, where her unusual harmonic sense shines through the clearest, and as somebody who has long cut his teeth on hearing Tony Levin or Trey Gunn warble his way around idiosyncratic Robert Fripp harmonics, this strikes me very much as a feature and not a bug. And hey, while I wouldn't recommend for most people to start here, if your first exposure to her was through The Last Waltz, I could think of worse entry points.

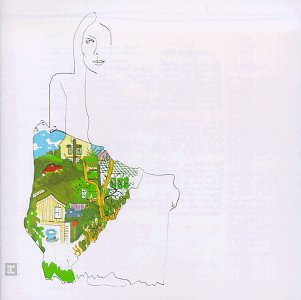

Song To A Seagull - 1968 Reprise

B

(Very Good)

Clouds - 1969 Reprise

B

(Very Good)

Ladies Of The Canyon - 1970 Reprise

D

(Great / Very Good)

*Blue - 1971 Reprise*

E

(Great)

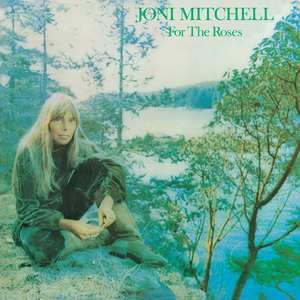

For The Roses - 1972 Asylum

D

(Great / Very Good)

Court And Spark - 1974 Asylum

E

(Great)

Miles Of Aisles - 1974 Asylum

C

(Very Good / Great)

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns - 1975 Asylum

D

(Great / Very Good)

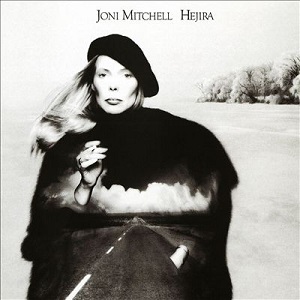

Hejira - 1976 Asylum

D

(Great / Very Good)